Bidtique’s bidding hall of fame and shame: what we can learn from famous and infamous bids

Every bid tells a story and has a story behind how it came to be. Some are masterclasses in vision and alignment; others are cautionary tales in hubris, politics, or crappy timing.

Whether it’s cities, corporations, or governments doing the pitching, the same fundamentals apply to all of us working in tenders and proposals: understand your client, get your strategy right, and don’t believe your own hype.

Here’s a look at some famous and infamous bids in Bidtique’s ‘Hall of Fame and Shame’

and what they teach us about winning work, influence, and reputation.

HALL OF FAME: THE GOATs (Greatest of all time)

1. Sydney 2000 Olympics bid

Still the gold standard for national bidding.

Sydney’s win wasn’t about glossy presentations or inflated projections; it was about vision, credibility, and emotional connection. The campaign combined genuine community support, powerful storytelling, and clear legacy benefits for sport, tourism, and infrastructure.

Lesson: Winning bids make evaluators feel something. The best bids align logic and emotion around a believable, benefits-led story.

Further reading

The Bid: How Australia Won the 2000 Games – Rod McGeoch and Geoff Donaghy

Sydney 2000 Olympic bid – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bids_for_the_2000_Summer_Olympics

2. Lendlease unsolicited proposal – NorthConnex Tunnel

An example of how to make an unsolicited proposal work under NSW Government guidelines. Lendlease identified a long-standing problem in the network: Pennant Hills Road, then regularly ranked as one of Australia’s worst and most dangerous roads. Heavy freight, school zones, pedestrian risks, diesel fumes, and traffic lights every few hundred metres made it a corridor in urgent need of a structural fix.

Lendlease’s unsolicited proposal offered exactly that. Crucially, it delivered a unique solution – the test NSW uses to assess unsolicited bids. The solution had to be something only Lendlease could credibly deliver at that time, offering genuine added value that government could not obtain through a standard open tender.

The NorthConnex concept aligned tightly with state priorities on freight efficiency, safety and liveability, and was packaged to demonstrate realistic risk transfer and clear public benefit through a public-private partnership model.

The result: thousands of trucks removed from Pennant Hills Road each day, improved air quality, safer school zones, quieter neighbourhoods, and faster freight movements between the M1 and M2.

Lesson: Unsolicited bids must be unique. They succeed when they solve your client’s problem in a way no one else can, not when they showcase your ambition.

Further reading

NorthConnex: NSW Government: https://www.transport.nsw.gov.au/projects/current-projects/northconnex

NorthConnex: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NorthConnex

Pennant Hills Road: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennant_Hills_Road

3. Australia and New Zealand: FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023

If Australia’s 2022 men’s World Cup bid belongs in the infamy column (see more below) the 2023 Women’s World Cup co-hosted by Australia and New Zealand is the perfect counterpoint.

Where the men’s bid was glossy, naïve and politically tone-deaf, the women’s bid was strategically aligned, values-driven and culturally resonant.

The result was not just a successful bid, but a watershed moment for women’s sport.

The tournament delivered record-breaking crowds and broadcast numbers. The Australian Women’s team ignited “Matildas fever” – a surge of public engagement unlike anything previously seen in Australian women’s sport. The semifinal between Australia and England became the most-watched television event in Australian history, overtaking decades of Olympics, AFL, NRL and cricket dominance.

Participation, attendance, merchandise sales, and government investment surged. This wasn’t just an event; it was a cultural shift.

Lesson: The 2023 Women’s World Cup bid succeeded because it aligned with global and local priorities: gender equality, participation uplift, social impact and authentic community support. It understood the landscape and offered something the world actually wanted.

Further reading

Bids for the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bids_for_the_2023_FIFA_Women%27s_World_Cup

Matildas fever: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matildas_fever

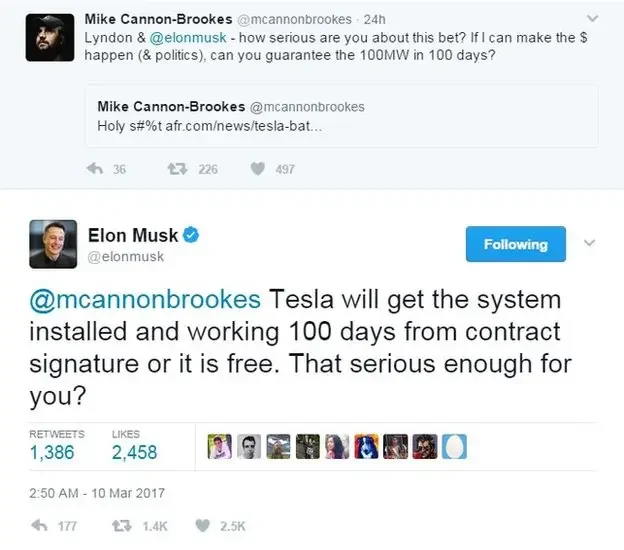

4. Tesla’s 2017 ‘100-day battery’ bid: a bold unsolicited proposal that paid off

The tweet that started it all: https://x.com/elonmusk/status/840032197637685249

In early 2017, South Australia was reeling from a series of energy failures: the state-wide blackout of September 2016, rolling outages, load-shedding events and political finger-pointing. The state urgently needed a grid-stabilising solution, but options were expensive, slow or politically fraught.

Enter Elon Musk.

After that public Twitter exchange with Atlassian’s Mike Cannon-Brookes and the SA Government, Tesla put forward what was effectively an unsolicited proposal:

Build a 100 MW grid battery in 100 days from contract signing, or it would be free.

It was a bid engineered for both headlines and procurement logic:

a simple, measurable performance commitment

a high-value downside guarantee

minimal risk transfer to government

immediate public and political support

a solution aligned exactly with the state’s energy stability needs.

The Hornsdale Power Reserve was delivered ahead of schedule in December 2017. It became a global benchmark, reduced grid stabilisation costs, and reshaped thinking on renewable energy storage.

Lesson: Tesla’s bid succeeded because it paired ambition with a hard delivery guarantee. Clear scoping, bold but credible risk allocation, and a direct response to a burning client need turned what looked like a stunt into a defining infrastructure success.

Further reading

Hornsdale Power Reserve: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hornsdale_Power_Reserve

ABC News: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-01/elon-musks-battery-bet-pays-off/9215590

HALL OF SHAME: THE SHOCKERS

5. Melbourne’s 2026 Commonwealth Games bid backflip: when bad modelling sinks a project before it starts

As a counterpoint to Sydney’s Olympic triumph, Melbourne’s withdrawal from hosting the 2026 Commonwealth Games shows what happens when modelling, consultation and scope control simply aren’t there.

Victoria pitched a distributed, multi-regional Games across Geelong, Ballarat, Bendigo, Gippsland and Shepparton. It was marketed as a celebration of regional development. The problem? The planning and modelling were deeply flawed from the start.

Independent reviews later revealed that:

key cost assumptions were incomplete or optimistic

regional councils weren’t properly consulted

the multi-town model required multiple major builds and upgrades, athlete villages and infrastructure that didn’t exist

splitting the Games across five regions sent projected costs spiralling.

The result: a blowout from $2.6 billion to $6 - 7 billion or more (!). The Victorian Government withdrew entirely, triggering a dispute with the Commonwealth Games Federation and significant political and reputational fallout.

Lesson: If your foundational modelling is flawed, everything collapses. Bids fail when scope is driven by excitement rather than evidence.

Ask before you bid.

Not the excited people. Not the loudest people.

Ask the people in your organisation who actually know what it takes to deliver.

A five-minute conversation upfront can prevent a multi-billion-dollar catastrophe later.

Further reading

2026 Commonwealth Games https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2026_Commonwealth_Games

6. Lane Cove Tunnel: the bid that collapsed under its own assumptions

If NorthConnex is the model of a well-aligned unsolicited proposal, the Lane Cove Tunnel shows what happens when a bid is built on optimistic modelling rather than real conditions.

The winning consortium paid the NSW Government $1.6 billion for the concession, based on traffic and revenue forecasts that proved wildly unrealistic. Actual traffic was around 30 percent lower than projected. Within a few years, the company collapsed and the tunnel was sold for $630 million (well under it’s bid ‘value).

Persistent leaking and water ingress have required repeated maintenance, including extensive night-time reconcreting planned for 2025. The two-lane-each-way design was never sufficient for long-term growth, meaning long term capacity constraints were inevitable even if the modelling had been right.

Lesson: Bids built on wishful thinking eventually crack. Robust modelling and realistic design choices matter more than competitive gloss.

Further reading

Lane Cove Tunnel: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lane_Cove_Tunnel

Lane Cove Tunnel sold for $630 million - ABC News

7. Australia’s failed 2022 FIFA men’s World Cup bid

An infamous proposal failure.

According to former FIFA President Sepp Blatter:

Australia had no chance. Not a chance. Never.

Despite spending $46 million, Australia received one vote.

As journalist Steve Cannane summarised:

’Australia was never competitive for broadcasters, never aligned to FIFA’s commercial priorities, and fatally overlooked the political realities of global football bidding’.

Lesson: Don’t confuse form with substance. Environmental scanning and political awareness matter as much as presentation quality.

Further reading

Australia 2022 bid: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australia_2022_FIFA_World_Cup_bid

ABC analysis: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-05/australias-world-cup-bid-was-doomed-from-the-start/6521916

8. SolarReserve’s Port Augusta solar thermal bid:

a winning bid that couldn’t be delivered

Sadly, not many sunny days following this outcome.

The same energy crisis that made Tesla’s 100-day bid possible also produced another headline project: SolarReserve’s $650 million Port Augusta solar thermal plant.

On paper, it was everything the moment demanded: dispatchable renewable power, regional jobs, and a symbolic replacement for the coal-fired Northern Power Station.

SolarReserve won the tender with an impressive, visionary bid.

But it was never fundable.

Debt financing never materialised, investors doubted viability, cost assumptions were fragile, and the company’s global portfolio was already under strain.

By 2019, the entire project collapsed.

Lesson: A bid is not successful when it’s awarded. It is successful when it is deliverable. Procurement sometimes rewards ‘shiny’; actual delivery demands substance.

Further reading

Aurora Solar Thermal Power Project: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_power_in_South_Australia#Aurora_Solar_Thermal_Power_Project

Final thought

The GOATs and the shockers all teach the same lesson: bidding isn’t magic, and it isn’t guesswork.

The winners knew the audience, solved the real problem and delivered what they promised.

The losers didn’t.

If you take nothing else from this hall of fame and shame, take this: do the thinking, test the assumptions, and only bid what you can stand behind. Your reputation lasts longer than the tender.

Happy bidding!